We are in the middle of a synchronized downturn. Analysis of the quarter or quarter change in GDP globally and in the US makes grim reading – worse than anything observed in the past.

Partially, this is due to the global reduction in activity through lockdown restrictions to mobility. Yet, if equities were to be considered as a barometer for future global activity, this would appear to be the shortest recession in history.

We can spotlight the performance of the S&P 500 Index. From being down approximately 30%, the market crossed its previous peak of 3389 on 18 August 2020. And with the backdrop of increasing infections globally, especially in the United States, and the upcoming presidential election in November. Analysis shows a real disconnect between the financial assets and the real-world economy. In addition, the stocks on NASDAQ, primarily small tech companies, have recovered an eye-watering 78%, after a drop of 28%.

In response to the Covid-19 crisis, central governments across the globe have unveiled massive fiscal and stimulus packages to help sustain their economies, especially from threats to the labour market.

The scale of stimulus has even dwarfed those created during the global financial crisis 2008. The stimulus packages in United States amount to approximately 13% of GDP, with the UK at 5% of GDP. The comparable figures in 2008 were 5.9% and 1.5% respectively.

A consistent concern expressed at this tidal flow of liquidity being provided is what happens in the wash. The bull run in equities and the compression of yields of corporate bonds is often attributed to the stimulus provided by central banks along with lower interest rates, which can be considered as a form of stimulus as well. Post the implementation of the emergency measures since March 2020, we see the same pattern re-occur, albeit on steroids.

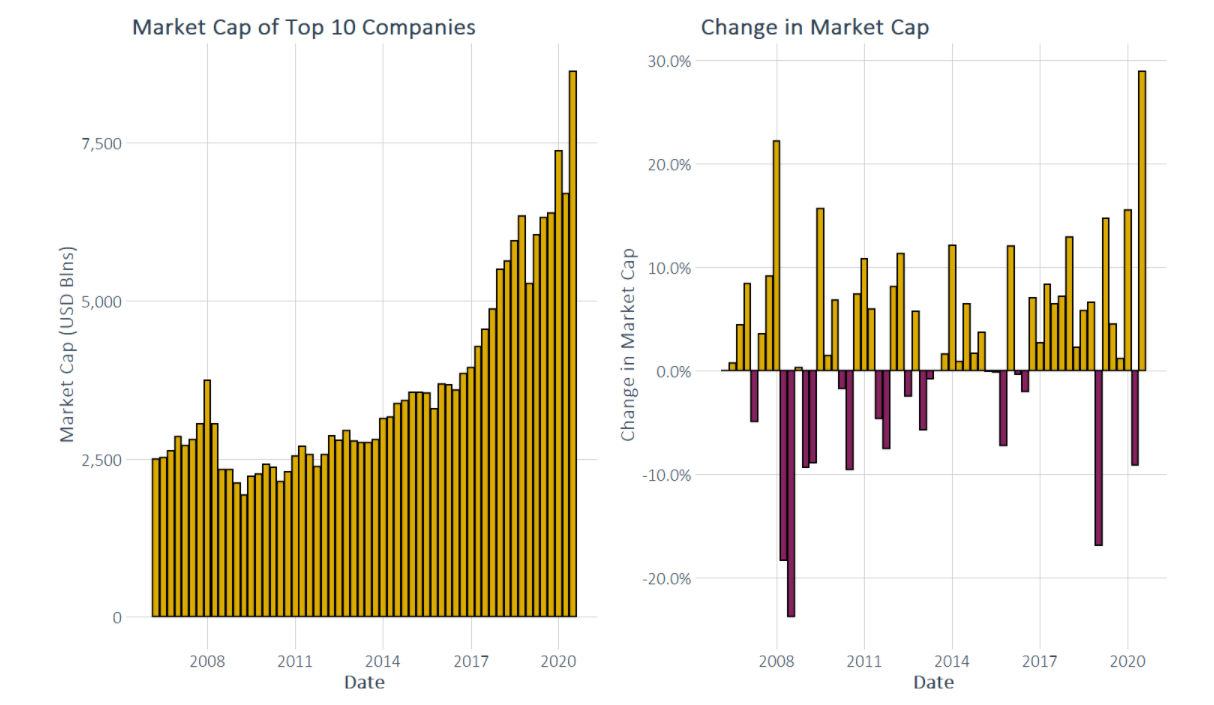

The market participants have been especially selective. Consider [above] a chart of the 10 largest companies in the world and their market capitalisation as well as the change quarter on quarter. It is incredible to note that capitalisation of the top 10 companies is the highest that it has ever been and up almost 30% from the previous quarter. While it is understandable that after a severe shock to markets, there is generally a rebound in the valuations, in 2020 even compared to previous crises, the change in value appears egregious.

The market participants have been especially selective. Consider [above] a chart of the 10 largest companies in the world and their market capitalisation as well as the change quarter on quarter. It is incredible to note that capitalisation of the top 10 companies is the highest that it has ever been and up almost 30% from the previous quarter. While it is understandable that after a severe shock to markets, there is generally a rebound in the valuations, in 2020 even compared to previous crises, the change in value appears egregious.

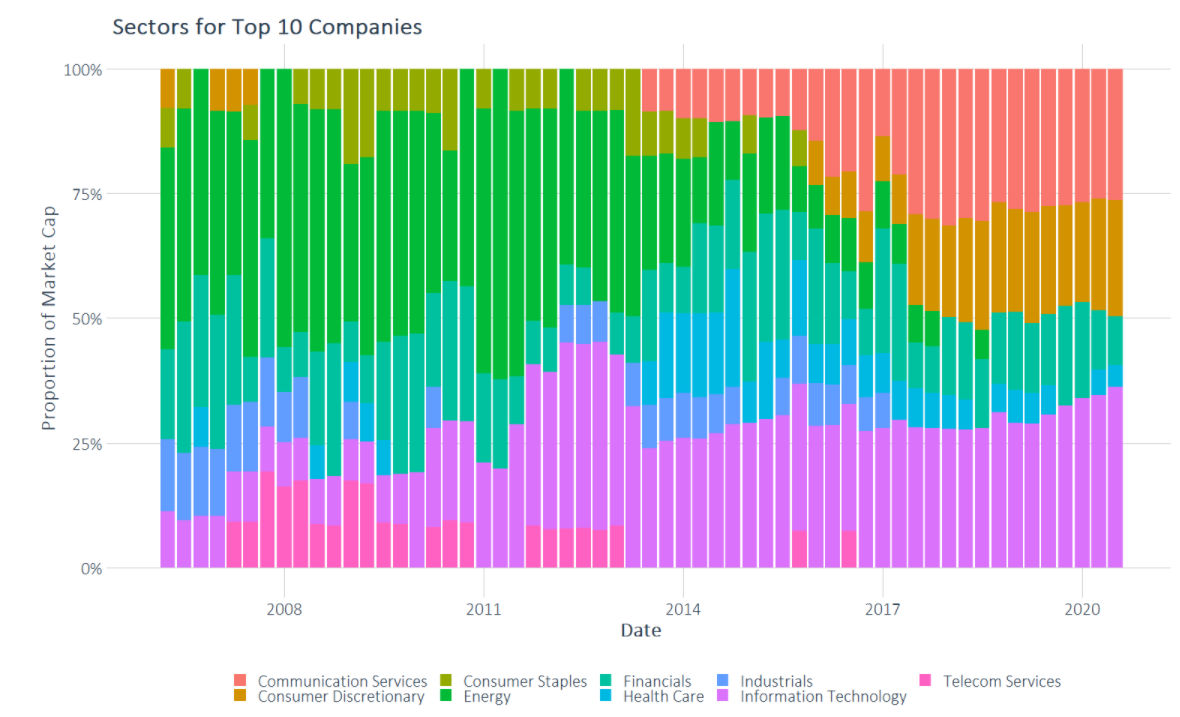

In addition, we can look at the composition of these 10 companies [above]. Since the time we have collected this data, which starts from Q2 2006, the companies have been composed of seven GICS sectors whereas as of Q2 2020, it composed of four sectors.

In addition, we can look at the composition of these 10 companies [above]. Since the time we have collected this data, which starts from Q2 2006, the companies have been composed of seven GICS sectors whereas as of Q2 2020, it composed of four sectors.

Out of the 10 companies, seven of them are technology enabled and include the likes of Facebook, Apple, Google, Microsoft and Amazon. The non-tech companies include Berkshire Hathaway, Visa and Johnson & Johnson.

Like any crisis, the Covid-19 pandemic has been a catalyst for change, being referred to even as the ‘Great Acceleration’. While it is immediate in some areas, as in the change in consumer behaviour and adoption of e-commerce, in others we may not see the impact in a few years.

What all economic participants realise and agree on is that there is no going back to pre-Covid in terms of business models, as well as consumer preferences and behaviours. What we do expect to see are the following:

- Shift to value and essentials. This, being a social crisis, affects the real economy more than previous crises. Uncertainty about prospects and health concerns, has shifted focus to being mindful of spending and researching brand and product choices before buying

- Increased and persistent utilisation of digital channels. Becoming a requirement due to restricted mobility, this is a trend which appears to have been adopted the most by consumers. The growth has been across the board for all kinds of products and across all age groups.

- Decreasing brand loyalty. Due to supply chain disruptions for certain products and brands, consumers could not find their preferred products at their preferred retailer. This has had an impact on brand loyalty through brand switches, with value, availability and quality being the main drivers.

- A home-based economy. Consumers have increased their consumption of in-home offerings across all sectors. This is not linked to easing of government restrictions, rather than waiting on guidance from medical authorities.

Given these changes, it is only logical and natural that companies which have already adopted such consumer preferences, within their business processes or have changed rapidly to do so, have benefited.

But, as we saw in the lead up to the dot-com bubble in the 1990s – a period of massive growth in the use and adoption of the internet – any company which purports to do business online or related to e-commerce, cloud computing or disruptive growth has seen huge uptake, resulting in near-egregious valuations.

So, when we look at headlines blaring about the peaks made by S&P 500, one tends to forget that it’s mainly the tech-driven companies which have been bought – even over bought maybe. As with any such exuberance with the advent of the new, there is always a dampener as business models get fixed into place. Winners and losers among the adopters will arise, leading to a shake-up in markets.

Looking forward, we expect to see some volatility coming through in markets, as investors rationalise and reassess. But this only serves to separate the wheat from the chaff – leading to the re-establishment of new order.

As investors, we need to be wary and congnizant of these changes and constantly re-assess the relative risks that arise. It is tempting and often simpler to go with the flow. But not jumping the FOMO bandwagon could possibly be the way forward.

Learn more about Dynamic Planner’s benchmark asset allocation.